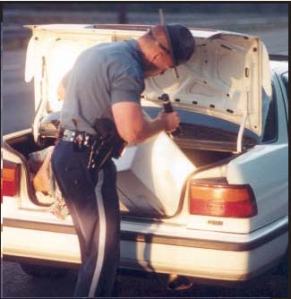

Vehicle Searches Incident to Arrest

June 2, 2010

When can police officers search a vehicle? When they are arresting the occupant of the vehicle. In 1981, the United States Supreme Court in the case of New York v. Belton, 453 U.S. 454, stated “when a policeman has made a lawful custodial arrest of the occupant of an automobile, he may as a contemporaneous incident of that arrest, search the passengers compartment of that automobile and any containers therein.” The court rendered this decision based upon a “generalization that articles inside the relatively narrow passenger compartment of an automobile are in fact generally within the area in to which an arrestee might reach in order to grab a weapon or evidentiary item.” Fran Simmel v. California 395 U.S. 763.

When can police officers search a vehicle? When they are arresting the occupant of the vehicle. In 1981, the United States Supreme Court in the case of New York v. Belton, 453 U.S. 454, stated “when a policeman has made a lawful custodial arrest of the occupant of an automobile, he may as a contemporaneous incident of that arrest, search the passengers compartment of that automobile and any containers therein.” The court rendered this decision based upon a “generalization that articles inside the relatively narrow passenger compartment of an automobile are in fact generally within the area in to which an arrestee might reach in order to grab a weapon or evidentiary item.” Fran Simmel v. California 395 U.S. 763.

In a decision of April 2009, the United States Supreme Court in the case of Arizona v. Grant narrowed the circumstances under which there can be a search incident to arrest. In the Grant decision the United States Supreme Court stated that police may now search a vehicle incident to the arrest of the occupant of the vehicle only if the person being arrested is “unsecured and within reaching distance of the passenger compartment at the time of the search” or “it is reasonable to believe the (the passenger compartment) contains evidence of the arrest.”

The court stated in this decision “when the justifications are absent, a search of the arrestee’s vehicle will be unreasonable unless police obtain a warrant or show that another exception to the warrant requirement applies.”

In the a situation where the police arrest an individual driving a vehicle, place him custody, in hand cuffs and remove him from the vehicle and place him in the squad car there would be no reason for the police to engage in a warrantless search of the occupants vehicle unless a crime was committed involving contraband or a gun and police were searching for the contraband or gun.

Unfortunately this decision has not filtered down to most police organizations. Police routinely search vehicles when they put an occupant under arrest without justification. The prosecutors then seek to use any evidence obtained from said searches in the prosecution of the driver or other occupant of the vehicle. Based on this new United States Supreme Court decision, motions can be made to preclude the entry into evidence of material obtained through improper searches. If you or a friend or family member have been arrested and a vehicle was improperly searched feel free to give our office a call at 1-800-344-6431 or email us.

Strip Searches: The Court Of Appeals Says No, No!

May 29, 2010

Is it a common practice for police to use a search warrant to strip search every person in a location without a strong indication the place is “devoted” to criminal activity.

Is it a common practice for police to use a search warrant to strip search every person in a location without a strong indication the place is “devoted” to criminal activity.

Recently the New York State Court Of Appeals said that drugs found on one man in 2006 during a raid of an apartment in Syracuse can not be used as evidence. Robert Mothersel and six other individuals were stripped searched on this occasion.

The New State Court Of Appeals said broad-based search warrants are unconstitutional unless police surveillance shows every person at a particular location would have contraband or criminal evidence on them. In the case involving Robert Mothersel, the court found the strip searches were inappropriate. Mr. Mothersel was stripped searched and a body cavity search was conducted. Drugs were found in his buttocks. At the time of the search Mr. Mothersel was not under arrest. The Court of Appeals found the drugs found in Mr. Mothersel’s buttocks were illegally obtained and could not be used against him in court.

A Syracuse detective involved in the case stated at a court hearing “in the execution of hundreds of all-person-present warrants, the people were routinely stripped searched and required to facilitate the examination of their anal and genital cavities.”

Judge Libbman, writing for the New York Court Of Appeals, described circumstances wherin such broad-based strip search warrants would be approved.

He stated “we think it is clear that surveillance of a location may yield a factual basis to infer with the requisite force that the place is devoted to an ongoing illicit purpose, such as the manufacturing or marketing of narcotics, . . . and that all those present at the time of the contemplated search will probably in possession of contraband or other specified evidence of illegality.”

Strip searches, and especially body cavity searches, can amount to the deprivation of the most basic rights of privacy a United States citizen should expect. We hope you never experience this humiliating situation. If you or a family member were improperly subject to an outrageous violation of your right to privacy feel free to call us at 1-800-344-6431 or contact us by email. We will protect your rights.

![]()

Right now, it depends which part of New York you live in. In Westchester and Albany, the police do not need a warrant to place a GPS tracking device on your car, but in Nassau County they do.

On March 24th, the New York Court of Appeals heard oral arguments (video here) in the case of People v. Weaver, which will probably lay out a uniform rule for all of New York State (the Supreme Court of the United States has not yet ruled on the matter). In that case, the Defendant is appealing of the affirmation of his conviction by the Appellate Division, 3rd Dept. People v. Weaver, 52 A.D.3d 138 (3d Dept. 2008).

In this case, Albany police secretly placed a GPS tracking device on the Defendant’s car to track his movements without acquiring a search warrant beforehand. The issue in the case is whether tracking someone with a GPS device constitutes a “search.” If it does, then the police must either get a warrant first or justify their decision not to obtain a warrant under one of the established warrant requirement exceptions. If it is not a search, then the Fourth Amendment would not be implicated at all and no warrant would be required.

The trial court and the Appellate Division reasoned that placing the GPS tracking device on the car was not constitute a search and thus did not require a warrant because the police were not learning anything from the tracking device that they could not have learned by simply following the car. The courts held that since anyone can follow any car on the road, individuals do not have a “reasonable expectation of privacy” that the location of their cars on the roads will remain a secret.

During the oral arguments in the Weaver case, Chief Judge Lippman asked the attorney for the government whether he would see any constitutional problem if the police decided to work with car dealerships to install GPS tracking devices on everyone’s car to watch their every vehicular movement. He elicited an admission by the government lawyer that his position was that such a practice would not offend individuals’ “reasonable expectation of privacy” under either the New York or U.S. Constitutions.

My legal e-pen pal, James Maloney, Esq., alerted me to this case and recently watched oral arguments as well, and predicted that the new Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman will pen a majority opinion finding that surreptitiously installing a GPS tracking device on a car does constitute a search and would ordinarily require a warrant absent some kind of exigent circumstances (emergency). Or, even if he does not write a majority opinion, that he would write a strong dissent arguing that placing a GPS tracking device on a car does constitute a search.

In this case, the danger of a limitless right by the police to track individuals’ every movement justifies a constitutional requirement that they obtain a warrant before doing so in order to avoid abuses.

As always, if you need criminal defense help or feel that you are being investigated by the police for a crime, you are invited to contact our office.

Update 5/12/09: I posted one day too early. I have not gotten to read the case yet, but apparantly the Court of Appeals just issued their decision in this case, finding that the New York Constitution does indeed prohibit warantless placement of GPS tracking devices without a showing of Exigent Circumstances by police. LINK.

Picture courtesy of consumertracking.com. As always, if you need help with any criminal matter, you are invited to contact our office.

Last week, the Supreme Court announced the groundbreaking decision of Arizona v. Gant, significantly limiting the police’s ability to conduct searches of automobiles “incident to a lawful arrest” without either a warrant or probable cause. Before the Gant case, however, New York courts have consistently interpreted the State Constitution much more strictly, in this regard, than the Supreme Court had interpreted the U.S. Constitution.

Last week, the Supreme Court announced the groundbreaking decision of Arizona v. Gant, significantly limiting the police’s ability to conduct searches of automobiles “incident to a lawful arrest” without either a warrant or probable cause. Before the Gant case, however, New York courts have consistently interpreted the State Constitution much more strictly, in this regard, than the Supreme Court had interpreted the U.S. Constitution.

This post will explore whether the new Gant decision makes the national rule regarding incident-to-arrest searches more lenient, as strict as New York’s rule, or stricter than New York, which would invalidate the New York rule to the extent that it was more lenient than the new Gant rule. This post will conclude that the Supreme Court’s new rule in Gant is still more lenient than New York’s rule, and that New York’s search-incident-to-arrest jurisprudence will probably not be affected by the holding in Gant.

For a nice summary of the development of the Supreme Court’s rules with regard to searches of automobiles incident to a lawful arrest, see the first part of Evidence ProfBlogger’s post at PrawfsBlawg, Coming Out of the Closet: How Arizona v. Gant Could Lead to the Shrinking of the Scope of Searches Incident to Lawful Home Arrests.

In short, before Gant was decided on Tuesday, the national rule, established by the Chimel case, was that was that incident to any lawful arrest, police may search “the area from within which he [an arrestee] might gain possession of a weapon or destructible evidence.” In the context of car arrests, the Court, in New York v. Belton, made a bright line rule that “when a policeman has made a lawful custodial arrest of the occupant of an automobile, he may, as a contemporaneous incident of that arrest, search the passenger compartment of that automobile.” This right was automatic. It did not depend on the arrestee’s actual ability to reach a weapon or destructable evidence, nor did the police have to show probable cause or reasonable suspicion that the car was likely to contain evidence or a weapon.

These cases set a very low bar for what would constitute an “unreasonable search and seizure” in the context of a search-incident-to-arrest of an automobile. But New York has consistently interpreted its own Constitution more strictly, not adhering to the lenient bright line rule set by Belton.

People v Blasich, 541 N.E.2d 40 (1989), and, later, People v. Galak, 616 N.E.2d 842 (1993), have interpreted the New York State Constitution‘s “[s]ecurity against unreasonable searches, seizures and interceptions” provision (Article I, § 12) as follows: The Court of Appeals has held that the “search-incident-to-arrest exception to the warrant and probable cause requirements of our State Constitution… exist[] only to protect against the danger that an arrestee may gain access to a weapon or may be able to destroy or conceal critical evidence.” Blasich.

Alternatively, the Court held that police may search the car, even where the arrestee factually cannot reach it, where they have

“probable cause to believe that the vehicle contains contraband, evidence of the crime, a weapon or some means of escape. If so, a warrantless search of the vehicle is authorized, not as a search incident to arrest, but rather as a search falling within the automobile exception to the warrant requirement.” (emphasis added)

The Blasich court further held that “the proper inquiry in assessing the propriety of [the] search is simply whether the circumstances gave the officer probable cause to search the vehicle… Which of those crimes the officer selected when formally notifying the suspect that he was under arrest has little bearing on the matter.” In other words, it is immaterial whether the probable cause justifying the car search is also probable cause of the same offense that justified the initial arrest. As long as there is probable cause of some crime justifying the automobile search, the police may search it.

The question is whether the Supreme Court’s Gant decision last week brings up the U.S. Constitutional test for searches incident to arrest to the point where it is stricter than, more lenient than or the same as New York’s rule.

In order to answer that question, we must first understand what level of certainty the Supreme Court now requires the police to have that they will find evidence in the arrestee’s car. According to Gant, the police may only search an arrestee’s vehicle when when he “is unsecured and within reaching distance of the passenger compartment the time or the search”, or when it is “reasonable to believe that evidence of the offense of arrest might be found in the vehicle.” (emphasis added)

How certain must they be that evidence of the offense of arrest may be found in the car? The same level of certainty as “probable cause?” “Reasonable suspicion?” Some new test?

Orin Kerr offers a fundamental discussion of this question in a post at The Volokh Conspiracy, entitled When Is It “Reasonable to Believe” That Evidence Relevant to An Offense is In A Car? Does that Require Probable Cause, Reasonable Suspicion, or Something Else?.

In that post, he rules out the idea that “reason to believe” means probable cause because if that is what it meant, the search would be justified under the “automobile exception” to the warrant requirement irrespective of the “search incident to a lawful arrest” exception. Furthermore, he points out that Justice Alito’s dissent specifically distinguishes the “reason to believe” standard from “probable cause,” indicating that he understood the majority’s “reason to believe” test to be something other than probable cause.

I would add that even though the New York Court of Appeals in Blasich, above, uses the phrase “reason to believe” to mean “probable cause, I do not think it is necessarily relevant in determining the Supreme Court’s intended meaning when using the phrase “reasonable to believe.”

Professor Kerr also reasons that it is unlikely that Terry‘s “reasonable suspicion” test is the underlying meaning of “reason to believe.” As applied to the car search context, “reasonable suspicion” would probably be defined as “whether ‘a reasonably prudent man in the circumstances would be warranted in the belief’ that there was evidence relevant in the arrest in the passenger compartment of the car.” Prof. Kerr opines that this standard would seem difficult to apply in the context of a determination of whether a search for evidence is reasonable, in contrast with its simpler application in a Terry frisk, when the officer has to make a quick decision about whether the person in front of him may be concealing a weapon.

Prof. Kerr concludes that “reasonable to believe” is probably something less than probable cause, but it is not clear to him exactly what level of certainty it is.

“Reasonable to believe” is most likely less than probable cause. Partly, this is because, as Prof. Kerr pointed out, Justice Alito understood the majority this way in his dissent (and Stevens opinion in Gant also takes note of how influential the Brennan dissent in Belton was in shaping courts’ interpretation of the Belton majority). Also, if the majority opinion had intended to invoke the big gun, the probable cause standard, it should have and probably would have done so explicitly.

But there is another reason why this author believes that the court requires less than probable cause to justify the car search when the arrestee is secured. The fact that the court requires that the officer have a reasonable belief that evidence of the “offense of arrest” might be found in the car indicates that this level of certainty is not synonymous with probable cause. Because if it were, then the probable cause of whatever offense would justify the search of the car under the automobile exception, without the need to invoke the incident-to-arrest exception.

It is evident that the Court is trying to grant added protection to defendants by requiring that the reasonable belief must be that evidence of the offense of arrest will be found specifically because the justification for the search is something less than probable cause. Such a stringency in the search-incident-to-arrest doctrine would not be needed if probable cause that evidence would be found in the car were present and the automobile exception applied.

The court probably requires “offense of arrest” specific reasonable suspicion in order to limit the use of “pretextual stops,” where police pull someone over for some traffic offense, for which the driver could be arrested, because they want to find evidence of some unrelated offense, in a search of the vehicle in incident to that arrest.

All of that being said, it appears that New York’s rule is still stricter than the Supreme Court’s rule.

It may appear from the Court of Appeals’ Blasich decision, mentioned above, that New York is more lenient than the Gant case because it allows searches of secured arestees’ vehicles for any offense, while Gant only allows searches for evidence of the offense of arrest.

This is not so, however, because Blasich explicitly stated that the search of a secured arrestee’s car for evidence of any offense is not justified “as a search incident to arrest, but rather as a search falling within the automobile exception to the warrant requirement.” The New York rule, therefore, permits car searches supported by probable cause that evidence of any offense will be found, using the automobile exception. While Gant holds that police must reasonably believe that evidence of the offense of arrest might be found.

This author believes, therefore, that in situations where a suspect has been secured and police do not have probable cause that evidence of some crime will be found in the car, New York will continue to apply the stricter rule that police may not search the vehicle without a warrant. While outside New York, the new Gant rule will be followed that would allow a search of a secured arrestee’s vehicle when police have a reasonable belief that evidence of the offense for which the suspect was arrested might be found in the car.

Picture courtesy of howstuffworks.

I talking with my employer, Elliot Schlissel, Esq., about my post yesterday regarding the case of the Tenaha, TX police department’s use of apparently unreasonable searches and seizures to obtain money and property from travelers through their town to bolster their local budget. I told him that the individuals involved are being sued for violations of the victims’ civil rights. He suggested that those individuals involved may potentially be prosecuted criminally for violations of the Federal Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (“RICO”) law.

I talking with my employer, Elliot Schlissel, Esq., about my post yesterday regarding the case of the Tenaha, TX police department’s use of apparently unreasonable searches and seizures to obtain money and property from travelers through their town to bolster their local budget. I told him that the individuals involved are being sued for violations of the victims’ civil rights. He suggested that those individuals involved may potentially be prosecuted criminally for violations of the Federal Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (“RICO”) law.

After reviewing some of the basic RICO statutes, I think the U.S. Attorney’s office prosecutors may have a case against the officers and individuals involved.

The RICO law, 18 USC §1962(c), prohibits “any person employed by or associated with any enterprise engaged in… activities… which affect[] interstate… commerce, to conduct… such enterprise’s affairs through a pattern of racketeering activity…” (emphasis added)

§ 1961(1) defines a “racketeering activity” as

(A) any act or threat involving murder, kidnapping, gambling, arson, robbery, bribery, extortion, dealing in obscene matter, or dealing in a controlled substance… which is chargable under State law and punishable by imprisonment for more than one year [or] (B) any act which is indictable under any of the following provisions of title 18, United States Code: Section 201… (emphasis added)

One of the acts “indictable under any of the following provisions of title 18” is extortion, which is defined by § 1951(a) as when someone “obstructs, delays, or affects commerce or the movement of any article or commodity in commerce, by robbery or extortion or attempts or conspires so to do (sic)…” That section further defines extortion as “the obtaining of property from another, with his consent, induced by wrongful use of actual or threatened force, violence, or fear, or under color of official right.”

And § 1961(5) defines a “pattern of racketeering activity” as “at least two acts of [even the same] racketeering activity…”

While the town of Tenaha itself is not a proper subject of RICO prosecution because it is not a “person” under the RICO statute, the Marshall, Mayor, Constable and Shelby County D.A., in their individual capacities, would be proper “persons” for RICO prosecution. See Pelfresne v. Village of Rosemont, 22 F.Supp.2d 756, 761 (N.D. Ill. 1998).

If the facts are indeed as the San Antonio Express-News has reported, then over 140 motorists have been stopped and been “willingly” induced to sign over their property with the threat of bogus prosecutions for crimes they were never charged with and which involved searches that probably violated their fourth Amendment right to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures.

Furthermore, the Mayor’s comments defending the practice indicated that it was their intent to use these means to bolster the cash-strapped budget of the town’s police force. This implied that their the use of the Texas forfeiture statute to confiscate travelers’ money and property using abuses of their 4th Amendment rights was a coordinated conspiracy.

Travelers’ freedom to pass and bring property between states appears to have been impeded by “wrongful use of… fear… under color of official right.” If indeed this has occurred in over half of the 140 instances of the induced property forfeitures between 2006 and 2008, and it can be shown that the officials involved took part in at least two instances of extortion each, then it would appear that the Marshall, Constable, Mayor and D.A. in Tenaha and Shelby County may be susceptible to criminal (and perhaps civil) RICO prosecution.

At the very least, the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Texas ought to look into whether an investigation should be opened to determine if criminal RICO prosecution may be appropriate.

Picture courtesy of community-builder.

Police Stop, Search & Confiscate Everything You Have…?

March 12, 2009

The Chicago Tribune has just picked up on a story from over a month ago at mysanantonio.com. The Texas town of Tenaha is using a state forfeiture law that gives the police the right to seize any property used in a crime to bolster that department’s budget. Police officers have been using this law to stop cars traveling through their tiny (pop. about 1000) town and they have taken property from over 140 drivers between 2006 and 2008.

The Chicago Tribune has just picked up on a story from over a month ago at mysanantonio.com. The Texas town of Tenaha is using a state forfeiture law that gives the police the right to seize any property used in a crime to bolster that department’s budget. Police officers have been using this law to stop cars traveling through their tiny (pop. about 1000) town and they have taken property from over 140 drivers between 2006 and 2008.

They apparently told people that if they didn’t sign their property over to the police, they would press charges against them for money laundering or other crimes. One waiver said “In exchange for (respondent) signing the agreed order of forfeiture, the Shelby County District Attorney’s Office agrees to reject charges of money laundering pending at this time…”

Cynically, the mayor of the town said that the seizures allowed a cash-poor city the means to add a second police car in a two-policeman town and help pay for a new police station… “It’s always helpful to have any kind of income to expand your police force.”

Without probable cause that a crime has taken place, and exigent circumstances to justify why the police must search the car without a warrant, police may not search a person’s car unless they have a “reasonable suspicion” that a person poses a danger to the police officer. And even then, they may only pat down a person or search in their immediate vicinity to the extent that such a search may help them find any weapons that could be used against them. They may not search outside of that scope searching for evidence of any crime however. Terry v. Ohio.

In some cases, the only “factual basis” for the drug or money laundering “charges” was the presence of larger sums of money in the car. And even for that, they would have had to search the car to find the motorists’ expensive property or cash without any “reasonable suspicion” of a threat to the police officer. In such a situation, that would be unconstitutional as well.

Normally, the remedy for the police’s violation of someone’s 4th Amendment rights would be suppression of any evidence obtained throught that violation. But in this case, since the individuals chose to sign over their property to the police, and no charges were filed, there is no evidence to suppress. Thus, the only remedy for a violation of these people’s Constitutional rights is by civil remedy, a §1983 discrimination case.

Thus, David Guillory, attorney for the so-far eight plaintiffs in the lawsuit against the town of Tenaha, filed a §1983 Complaint in District Court seeking compensation for the town’s violation of his clients’ Fourth Amendment Constitutional rights.

In an effort to prevent such abuses by towns in the future, the Texas Senate Criminal Justice Committe has recommended several changes to the forfeiture laws there (p.71), including a shift of the burden of proof to the government in order to seize assets:

If the facts are proven to be as egregious as Mr. Guillory and the aforelinked articles suggest, I very much hope he is successful in his case against the town and that the State adopts more stringent rules to prevent abuses like these from happening in the future.

Picture Courtesy of Chicago Tribune

As I posted on Jan. 30th, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals recently decided the case of Maloney v. Cuomo. Jim Maloney (pictured, right) was charged with possession of nunchaku (“nunchucks”) in his Long Island, New York home. He challenged the constitutionality of New York’s ban on nunchaku possession on 2nd Amendment grounds. But the 2nd Circuit held that the 2nd Amendment’s prohibition against laws that infringe on the right to “keep and bear arms” (as interpreted in DC v. Heller) does not apply to state laws.

As I posted on Jan. 30th, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals recently decided the case of Maloney v. Cuomo. Jim Maloney (pictured, right) was charged with possession of nunchaku (“nunchucks”) in his Long Island, New York home. He challenged the constitutionality of New York’s ban on nunchaku possession on 2nd Amendment grounds. But the 2nd Circuit held that the 2nd Amendment’s prohibition against laws that infringe on the right to “keep and bear arms” (as interpreted in DC v. Heller) does not apply to state laws.

I have been in touch with Mr. Maloney, since my earlier post, about his plans to take his case to the Supreme Court. The good news is that the D.C. office of Kirkland & Ellis, LLP has taken the case and will handle Mr. Maloney’s petition. They will argue that the 2nd Amendment, like most other individual rights, should be incorporated against the States. Thus, he hopes that the Supreme Court will prohibit state infringement of the individual right to own a weapon, just as it prohibits Congressional infringement. Mr. Maloney has agreed to write a guest post, giving us some background on the New York nunchaku ban, his case, and his future plans with regard to his upcoming petition before the Supreme Court:

New York enacted a ban on nunchaku back in 1974, after the new phenomenon of martial-arts movies had made nunchaku suddenly popular among serious martial artists and gang members alike.

New York’s legislature and Governor (Malcolm Wilson) hastily decided to impose a total ban on the instrument. The sponsor of the bill to ban “chuka sticks,” Assemblyman Richard Ross, wrote that the nunchaku “is designed primarily as a weapon and has no purpose other than to maim or, in some instances, kill.” New York City Mayor Beame expressed virtually identical sentiments. Police chiefs and DAs from around the state all weighed in with similar comments, all condemning “chuka sticks.” Manhattan District Attorney Frank Hogan (Robert Morgenthau’s immediate predecessor) wrote that “there is no known use for chuka sticks other than as a weapon.”

Against this strong tide to ban nunchaku only two voices of dissent emerged. The State of New York’s own Division of Criminal Justice Services sent a memorandum to the Governor dated April 4, 1974, pointing out that nunchaku have legitimate uses in karate and other martial-arts training, and opining that “in view of the current interest and participation in these activities by many members of the public, it appears unreasonable–and perhaps even unconstitutional–to prohibit those who have a legitimate reason for possessing chuka sticks from doing so.” Both the Criminal Justice Services memorandum and a similar one from the New York County Lawyers’ Association recognized that nunchaku have legitimate uses, and urged that the legislation be redrafted to permit martial artists to possess nunchaku. But the memoranda did not accomplish their objective, and the total ban was enacted, going into effect on September 1, 1974.

However, within just a few years, courts in other jurisdictions began to recognize that nunchaku have legitimate uses. For example, in 1982, the Supreme Court of Hawaii wrote: “Given the present day uses of nunchaku sticks, we cannot say that the sole purpose of this instrumentality is to inflict death or bodily injury. . . . We believe that nunchaku sticks, as used in the martial arts, are socially acceptable and lawful behavior, especially here in Hawaii where the oriental culture and heritage play a very important role in society.” State v. Muliufi, 64 Haw. 485, 643 P.2d 546.

A year later, the District of Columbia Court of Appeals wrote: “Since we are making a ruling concerning a weapon which apparently has not previously been the subject of any published opinions in this jurisdiction, it is worth making a few further observations about the nunchaku. Like the courts of other jurisdictions, we are cognizant of the cultural and historical background of this Oriental agricultural implement-turned-weapon. We recognize that the nunchaku has socially acceptable uses within the context of martial arts and for the purpose of developing physical dexterity and coordination.” In re S.P., Jr., 465 A.2d 823, 827 (D.C. 1983).

Back in New York, the total ban on any and all possession of nunchaku, even in the privacy of one’s home for peaceful martial-arts practice, has continued to the present day. Most disturbingly, enforcement efforts targeting in-home possession have increased since the start of the new millennium.

A press release from the Office of the Attorney General of the State of New York dated October 17, 2002, indicated that a settlement between a martial-arts equipment supplier in Georgia and the New York Attorney General included the conditions that the company provide then-Attorney General Eliot Spitzer with a list of New York customers who had purchased “illegal” weapons, including nunchaku, and that the company deliver written notice to their New York customers advising them to surrender those illegal weapons to law enforcement agencies.

According to the press release, a similar settlement was reached with another martial-arts equipment supplier in 2000. The press release quoted Spitzer as saying that such weapons, which include nunchaku, “have no place on our streets or in our homes.” (Worry about your own home, Eliot.)

There have been at least two recent criminal prosecutions for simple in-home possession of “chuka sticks” here on Long Island, where I live.

In August 2000, Nassau County police performed a warrantless search of my home in Port Washington while I was not present, found a pair of nunchaku, and charged me with misdemeanor possession of same. Although I was never convicted of any crime, the charge lingered for nearly three years before being disposed.

In 2003, just after the charge was dismissed, and finding myself with “standing” to challenge the constitutionality of New York’s nunchaku ban as applied to simple in-home possession (and being an attorney with a background in constitutional law), I brought a case in federal court in the Eastern District of New York.

The court explicitly recognized that the criminal charge against me for possession of nunchaku “was based solely on in-home possession, and not supported by any allegations that the plaintiff had used the nunchaku in the commission of a crime; that he carried the nunchaku in public; or engaged in any other prohibited conduct in connection with said nunchaku.” The court concluded: “Thus, the only criminal activity alleged against the plaintiff was his possession of the nunchaku in his home.” Unfortunately, the court found that there is no constitutional right protecting that interest.

On appeal to the Second Circuit, that court held that the Second Amendment does not protect the right to bear arms as applied against the states, and that the state had a rational basis for prohibiting possessing nunchaku. They never addressed my specific argument that the state lacked a rational basis for prohibiting simple in-home possession. See the Elliot Schlissel New York Law Blog’s initial post, “Can New York Legally Forbid You to Own Nunchucks?” At this time, the D.C. office of Kirkland & Ellis LLP has agreed to represent me pro bono in filing a petition for certiorari which due in late April. Updates about the case may be found on my dedicated website, www.nunchalukaw.com.

The other local prosecution for simple in-home possession of nunchaku occurred in Suffolk County, and the events began right around the time that the prosecution against me was being disposed. According to a federal civil-rights complaint, on January 25, 2003, Suffolk County Police broke down the door of the home of a Hispanic family in Brentwood and began executing a search warrant to find “drugs” that were suspected at the location because of “frequent traffic” to and from the home. As it turned out, no drugs were found even after a thorough search including the use of dogs. The family’s home-based Avon business explained the frequent visitors to the home. But the police did find an old pair of nunchaku hanging in a closet, and the man of the house, who admitted to owning them, was subsequently charged with misdemeanor possession.

The charges against him were not disposed until March 2006,w hen he was given an ACD (“Adjournment in Contemplation of Dismissal”). As of the date of this post, the civil-rights case against the Suffolk County Police is scheduled to begin trial before Judge Wexler of the Eastern District on March 9, 2009.

It is clear form the foregoing that New York can and will enforce the criminal statutes, enacted in 1974, that ban possession of the nunchaku even in one’s home. Eliot Spitzer’s civil actions against the martial-arts equipment suppliers, coupled with the two recent prosecutions on Long Island for in-home possession, make it clear that martial artists who wish to acquire and keep nunchaku in their homes for practice or self-defense must risk the possibility of criminal charges that could lead to a year in prison for doing so. That has been the state of affairs in New York for some 35 years.

Whether it will continue is a question that will (I hope) soon be up to the Supreme Court.

-James M. Maloney is an attorney and solo practitioner in Port Washington, New York.

(Mr. Maloney makes no admission, nor should any be inferred, that the above-photo was taken in NY)

Just How Extreme Must Police Negligence Be to Suppress?

February 26, 2009

Our office does a lot of criminal defense work, so I am always interested in developments in 4th Amendment Search and Seizure law.

Our office does a lot of criminal defense work, so I am always interested in developments in 4th Amendment Search and Seizure law.

Last month, the Supreme Court made it more difficult for a defendant to have evidence suppressed in its decision in the case of Herring v. U.S. In that case, police consulted clerks in a neighboring county regarding the existance of an arrest warrant for Mr. Herring. They had not updated their system to reflect that an arrest warrant against Herring was not current. In reliance on the arrest warrant that they thought existed, police arrested Herring and found drugs and a gun. Herring moved to suppress the evidence against him because it was found in the course of an arrest that was not supported by a valid warrant.

In an opinion by Justice Scalia, the Supreme Court ruled that “the exclusionary rule serves to deter deliberate, reckless, or grossly negligent conduct, or in some circumstances recurring or systemic negligence.” However, the Court held that the quirky failure of the clerks in the neighboring county to update the warrant system was not “so objectively culpable as to require exclusion.”

The Fourth Amendment Blog reported on the Illinois Appellate Court case of People v. Morgan from two weeks ago where the police tried to rely on Herring to avoid the exclusion of certain evidence of drug crimes that the police found while executing an invalid search warrant at Morgan’s home. There, the police relied on a list of search warrants that was up to three days old, rather than following their own procedure of printing out an updated list of valid search warrants every day.

Quite appropriately in my opinion, the Illinois appellate court reversed the trial court’s decision not to suppress the evidence. It held that Herring’s ruling was not applicable to the facts surrounding the search of Morgan’s home.

-

In Herring, the error in updating the warrant records was made by a clerk, not by the authors actually executing the warrant, as was the case with Morgan. Since the mistake was not made by police officers, exclusion of the evidence couldn’t meaningfully deter the not-systematically-negligent conduct of those non-police officers.

-

In Herring, the officers’ reliance on the warrant was not negligent because they were told it was valid by the clerk. But the officers were negligent in Morgan because they used an up to three day old warrant list without even attempting to verify the continued validity of the search warrant against Morgan.

-

The mistake that led to the out-of-date warrant in Herring was merely negligent, and therefore would not be meaningfully deterred by excluding the evidence obtained in the course of executing that warrant. But in Morgan, Exclusion of the evidence would lead to meaningful deterrence because it will motivate officers to be careful to use up-to-date warrant lists, as per their own department’s policy.

Herring was not meant, by the Supreme Court, to give carte blanche approval of police negilgence in the execution of warrants and should not be used that way. Society’s need for order and protection from criminals is essential, but the power to invade private homes and detain people is a great and awesome power, and thus it comes with a heavy burden of responsibility to exercise that power with great care.

Picture courtesy of fbi.gov.

Interesting Legal Links

February 4, 2009

Understanding when the police can frisk you: Nicole Black at Sui Generis offers her take on the pros and cons of the Supreme Court decision in Arizona v. Johnson, that I commented on here.

Understanding when the police can frisk you: Nicole Black at Sui Generis offers her take on the pros and cons of the Supreme Court decision in Arizona v. Johnson, that I commented on here.- A SWAT team invades an innocent family’s home when a VOIP-using prankster makes a fake 911 call: The Fourth Amendment blog: “SWATting” will get somebody killed because police enter without a warrant

- An Attorney who sues his former client for unpaid attorney’s fees gets counter-sued and has to pay the client $25,000: The Legal Profession Blog: Dangers of Suing a Client

When Can the Police Pat You Down?

January 28, 2009

As an appropriate follow up on this post from Monday about the Court of Appeals, Second Circuit’s decision a few days ago, the Supreme Court ruled on Monday about a related matter. In Arizona v. Johnson, the Supreme Court released a unanimous decision clarifying when a “pat down” for weapons is or is not in violation of the 4th Amendment prohibition against unreasonable searches and seizures.

As an appropriate follow up on this post from Monday about the Court of Appeals, Second Circuit’s decision a few days ago, the Supreme Court ruled on Monday about a related matter. In Arizona v. Johnson, the Supreme Court released a unanimous decision clarifying when a “pat down” for weapons is or is not in violation of the 4th Amendment prohibition against unreasonable searches and seizures.

In the case, a police officer pulled over a car for a routine traffic violation. After noticing some gang related clothing and unusual behavior by the passenger in the back seat, she began conversing with him and he revealed his gang affiliation with the Crips. She asked him to get out of the car, and fearing for her safety, she patted him down, whereupon she found a gun he was illegally possessing. Later on, this individual’s attorney moved to suppress the gun evidence, arguing that the pat down was an unreasonable search and seizure since she had no reasonable suspicion that he had or was about to engage in some criminal activity. All she had was a suspicion for her safety. The trial court allowed the evidence but the Arizona Court of Appeals said that since her suspicions were the result of a consensual conversation, the stop was no longer part of the traffic stop and that the officer therefore lost her ability to pat him down for fear of her own safety, barring a reasonable suspicion of criminal activity, which was absent in this case.

The Supreme Court reversed this Arizona Court of Appeals decision, and let the Trial Court’s decision to allow the pat down stand. They argued that “[a]n officer’s inquiries into matters unrelated to the justification for the traffic stop do not convert the encounter into something other than a lawful seizure, so long as the inquiries do not measurably extend the stop’s duration.”

As Professor Orin Kerr (one of the authors of my Criminal Procedure Casebook!) emphasizes in his post at The Volokh Conspiracy, “[t]he temporary seizure of driver and passengers ordinarily continues, and remains reasonable, for the duration of the stop. Normally, the stop ends when the police have no further need to control the scene, and inform the driver and passengers they are free to leave.” (emphasis added).

Combined with the 2nd Circuit’s decision on Monday, in New York, as long as the police stop a car for a traffic violation, and then see something that makes them suspicious that the occupants may have a weapon, they may pat down the occupants of the car and search the car if there’s some reasonable basis to think that illegal activity has or is about to take place.

These recent developments and decisions make it even more important to get a lawyer who understands the intricacies and the new developments in criminal procedure regarding what the police may and may not do in a traffic stop, if you get stopped for a DWI, or any other reason…

Picture courtesy of…

Established in 1978,

Established in 1978,